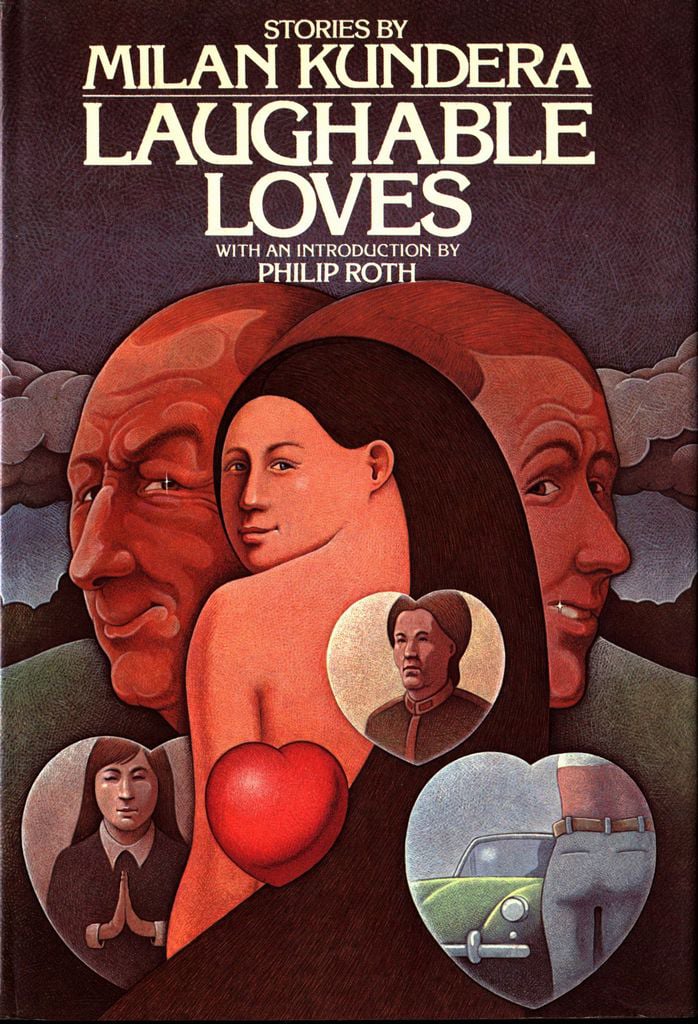

The collection of stories, originally published as three separate volumes in 1963, 1965, and 1968 and again in 1970 as a single volume for the publisher Žatva, eventually came out in 38 languages, being most frequently published in Spanish, French, Italian, German, and Chinese. In 1969 it was awarded the Czechoslovak Writers’ Association Prize.

I wrote them at the time when I was working on the play The Owners of the Keys. The subject was too serious and the work too laborious. Drama is the art form in which the most rigid rules of formal laws prevail, but it is also the one with the most practical concerns. I had a desire to escape it all, to feel free and have fun. And so, these three short stories arose which I liked all the more because they were able to strengthen the unserious spirit in me. I assumed that they were mainly whimsical stories, but some readers denied this. I therefore gave expression in the subtitle to my original illusion and their impression: they are anecdotes, but perhaps melancholy ones.

Milan Kundera, from the cover of Laughable Loves, 1963

EVER since the immortal „Good Soldier Schweik“ appeared, Czechoslovaks have had a reputation for paking fun at the various tyrants who have oppressed their nation jabbing them with pens dipped in acid-laced ink.

Milan Kundera is a writer in the „Schweik“ tradition, but with a touch of that other great Czech artist, Kafka.

He made his name in the heady days of the „Prague Spring“ which briefly blossomed in 1968. His writings ridiculed the authorian aspects of Communist rule and the clearly identified with Dubcek´s attemt create Socialism with a human face.“

His latest book „Laughable Loves“ is a collection of seen short stories concerning human love and psychological erotic games.

The play is effective in developing the plot, the principle of the play is explicitly named in the text. The story functions like a game machine that turns on the pivot of the punchline. However, this also reveals that this is not just any game, that it is played for more than a place in the table of successful shooters. It’s a game for real, for the fulfillment of life, and what’s more, for the fullness of living.

Kundera’s comedy, condensed into tragedy, thus contains a deeper subtext besides the emphasized triumph of life over the arbitrary action of the individual. The ease with which the narrator initially directs his own and others’ destinies is eventually revealed as fiction.

In short whimsical stories Kundera found a form sufficiently malleable and clear, capable of expressing his definite intention as fully as possible. He has discovered how to express in a playful, light way (and, it must be noted, in a masterly manner) something serious and perhaps even harsh about the life of people in today’s world, about what causes distress and dissatisfaction in it (...) He chooses words, associations and episodes judiciously, carefully constructs sentence after sentence, and holds the fate of his characters firmly in his hands. Yet the crucial importance does not rest on the plot. Kundera’s greatest achievement is that he manages to see and judge people, their desires and follies, with penetrating insight.

Source: Supraphon (profile on Youtube)

Supraphon released Laughable Loves in 2008 in spoken word form. The individual stories were narrated by Jan Kolařík, Igor Bareš, František Defler, Ladislav Lakomý, Antonín Přidal, and Marcela Vandrová. Listen to a short excerpt from the book.

The Milan Kundera Library is funded by the South Moravian Region and the City of Brno.

© 2024 Moravian Library in Brno