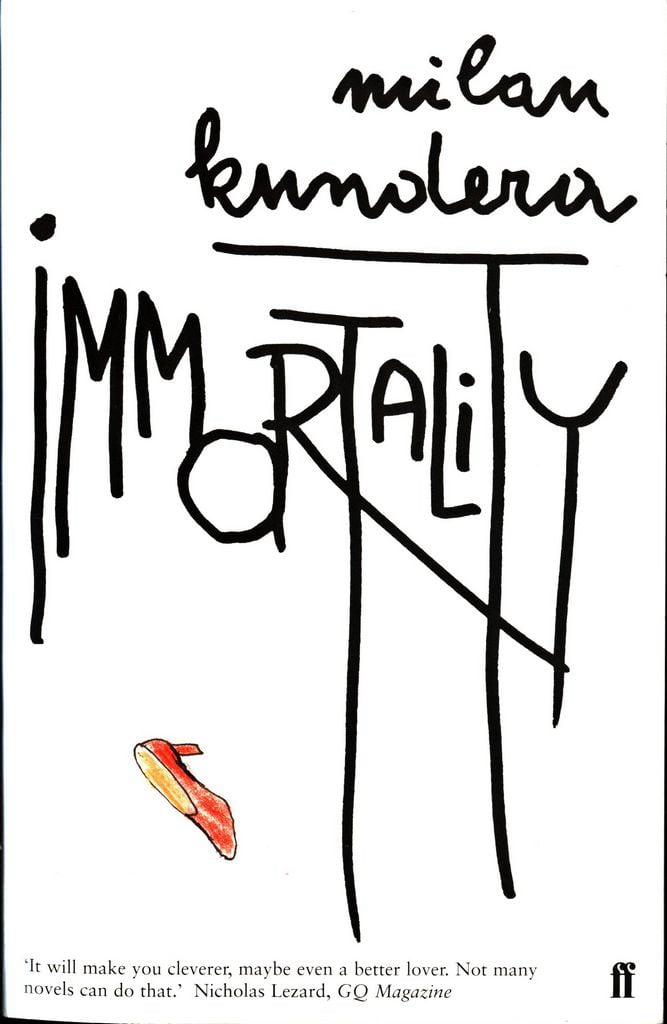

The last novel that Milan Kundera wrote in his native Czech was published in 44 languages and released firstly in France in 1990. That same year several German publishers brought out the title, and it was available to readers in two Italian editions. Spanish versions were published in Barcelona, Bogota, Santiago de Chile, Mexico City, and Buenos Aires. Two editions came out in 1990 with the publisher Circulo de Leitores in Lisbon and even three with the publisher Nova Frontiera in Buenos Aires. Turkey, Norway, and the Netherlands were not far behind. English readers only had to wait until the following year, when Harper Collins Publishers and Grove Weidenfeld Press in New York, and Faber and Faber in London and Calcutta released the book. In that year, the book won the British Independent Foreign Fiction Award. Three years later it received the Jaroslav Seifert Prize.

In any case, in Immortality we now have the richest and most fully drawn female character Kundera ever created, and the last glimpse of her is truly moving. To explain why, I would have to describe the plot, a task I seem to have neglected. But Kundera's elaborate meditation on the immortality of our gestures and forms uses so many resources that plot seems the least important aspect of this important and memorable book.

Jonathan Coe, The Guardian, 16. 5. 1991

She walked around the pool towards the exit. She passed the lifeguard, and after she had gone some three or four steps beyond him she turned her head, smiled, and waved to him. At that instant I felt a pang in my heart! That smile and that gesture belonged to a twenty- year-old girl! Her arm rose with bewitching ease. It was as if she were playfully tossing a brightly coloured ball to her lover. That smile and that gesture had charm and elegance, while the face and the body no longer had any charm. It was the charm of a gesture drowning in the charmlessness of the body. But the woman, though she must of course have realized that she was no longer beautiful, forgot that for the moment. There is a certain part of all of us that lives outside of time. Perhaps we become aware of our age only at exceptional moments and most of the time we are ageless. In any case, the instant she turned, smiled and waved to the young lifeguard (who couldn't control himself and burst out laughing), she was unaware of her age. The essence of her charm, independent of time, revealed itself for a second in that gesture and dazzled me. I was strangely moved. And then the word Agnes entered my mind. Agnes. I had never known a woman by that name.

Faber and Faber 2023, pp. 3-4

In Immortality, Kundera is explicit about his fictional method, which stands revealed at last, like the movement of one of those Swiss clocks with glass sides and back. Kundera dislikes the traditional concept of plot – which in this country goes back to Richardson – as a systém of cause and effect which unifies artistically the lives of characters.

Again and again, Kundera opens a new door in his novel - in a novel that doesn’t even want to exist anymore. But the abolition of the traditional plot has no equivalent in the abolition of all attitudes. On the contrary. A strict morality pervades all seven parts of the book; for example, a noticeable behind-the-scenes turn-up of the nose at journalism; and at the all-too-secular desires and lusts of modern man in a world between fashion fairs and mass media. By the end of Immortality, drunk on reading that has almost ceased to exist, your throat will be dry.

In the end, great deeds don't matter - a small gesture is enough to make you memorable. And Kundera may have moved up another rung on the ladder to immortality.

The style of the novel is reminiscent of a mixture of Sir Thomas Browne's elegant eclecticism and Kurt Vonnegut's wacky parables. The result is far more digestible than it might seem, and Kundera's wrenching analysis of the sentimental foibles of the human race will touch everyone from the buff exchange student from Mars to the novice in the reading club who hasn't yet been disgusted by postmodernist shenanigans. But be warned: this is a glittery fish where you have to pick every bone carefully, not a boneless herring that lands on your plate for free.

The Milan Kundera Library is funded by the South Moravian Region and the City of Brno.

© 2024 Moravian Library in Brno